Former editor of the Leicester Mercury and Derby Telegraph Keith Perch is now a lecturer at Derby University. Here he charts the catastrophic economic decline of one of the UK’s biggest regional daily newspapers

The Leicester Mercury has been one of the largest and most profitable regional newspapers in the UK. At its peak, it sold more than 150,000 copies a day, six nights a week, and declared more than £12m profit in a single year.

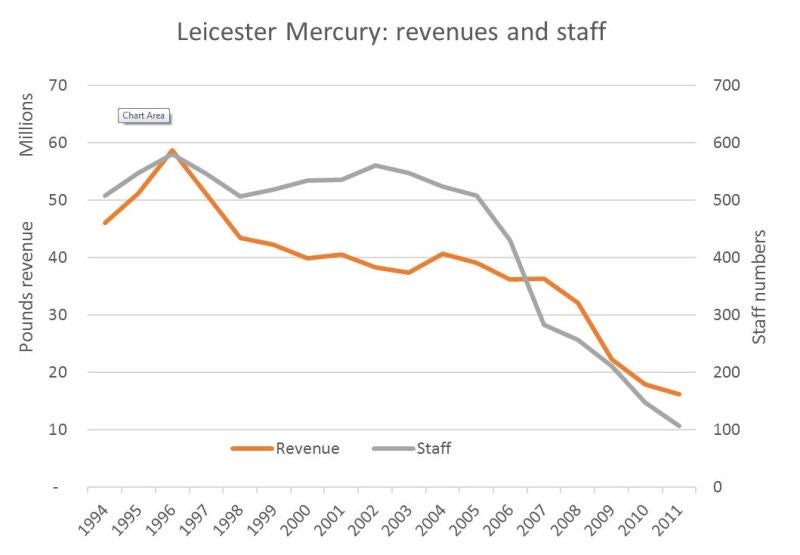

In 1996, it brought in almost £59m revenue and employed 581 staff . By 2011, its revenues had plummeted to £16m and it employed just 107 staff . Circulation has fallen from a high of 157,000 a day in 1984 to just 29,317 in the six months to July 2016.

In real terms, the company’s revenues had dropped more than 82 per cent, a figure matched almost exactly by the fall in staff.

Detailed figures of what happened at the Leicester Mercury are available until October 2011, but not afterwards. What is clear from that detail is the Leicester Mercury reflected the depth and severity of the monetary collapse of local newspapers in Britain.

Revenues of the Leicester Mercury have fallen significantly since their peak in 1996. When the figures are converted to current values (June 2014), it can be seen they have come down from £96m to £17m, a fall of 82 per cent. The main falls came in two different periods: the late 1990s and from 2005.

Revenues remained reasonably flat for the decade between 1994 and 2004 at about £40m. However, in the following seven years, revenues collapsed by 60 per cent and they are still falling today. This collapse was caused by a fundamental shift in the marketplace which has seen the business model of local and regional newspapers significantly undermined.

To understand why so much of local newspapers’ revenues disappeared, it is important to understand the make-up of those revenues.

Johnston Press (JP) is one of the UK’s largest local newspaper publishers, owning 13 paid-for dailies, and 195 paid-for weeklies, along with 40 free titles and 198 news websites.

JP spent the decade to 1997 buying newspaper businesses wherever they came up for sale, growing from a relatively small owner of weekly newspapers, to one of the country’s largest publishers, owning some of the UK’s best-known regional and local titles, including the Yorkshire Post, The Scotsman, Edinburgh Evening News, and the Belfast News Letter. The numerous acquisitions make annual comparisons difficult, but the buying spree had tailed off by 2006 and the fall in revenues from that point is clear.

The vast majority of revenues at JP in 2007 came from print advertising. A figure of about 70 per cent was typical for local and regional newspapers. It was this reliance on advertising which was to prove catastrophic for local newspapers when the internet really took off in the early 2000s. What exacerbated the situation was the categories of advertising on which local newspapers relied.

Just how much local newspapers relied on classified advertising can be seen from the fact it represented almost 50 per cent of the total revenues coming into the JP business. By the end of 2014, almost three-quarters of this revenue would disappear, bringing it down from £296m to just £79m – a fall of £217m.

The UK was in full recession by 2008, but, the economic downturn for newspapers began before that. As use of the internet grew, it became obvious classified advertising worked better online where it was fully searchable, always available and, relatively, cheap or free.

Newspapers believed they owned the property advertising market. JP stated in its 2007 annual report: “We expect our newspapers to continue to be the main source of promotional and marketing activity for the majority of estate agents.” They were wrong.

In the previous 12 months, JP had taken £80m in revenue for property advertising. In 2014, it took just £22.5m. In the same period, Rightmove had gone from zero revenue to more than £167m. Another online property site, Zoopla, which did not launch until 2008 has seen its revenues grow to more than £80m.

In the eight years after Zoopla launched, the two internet-only businesses grew online revenues to £247m between them: in contrast, JP grew its online property share to just £1.3m.

Of course, the newspapers could (and, indeed, did) set up stand-alone property websites, but these are businesses in their own right and are unlikely to be used to fund journalism.

In the Leicester Mercury’s accounts, it can be seen, while sites like Rightmove were rapidly growing their revenues, property revenues were declining at an alarming rate. The 2008 accounts record property revenues fell by 27 per cent during the year. The following year, property revenues fell by a further 50 per cent with the accounts stating the decrease was ‘approximately in line with industry declines due to the economic climate.’In total, the Mercury had lost 63 per cent of its property advertising in just two years.

Yet, despite the economic climate, Rightmove was seeing rapid growth. It was not just property advertising. In the four years to 2011, the Mercury lost 77 per cent of its recruitment advertising – the most expensive and profitable advertising it sold. The end result was in just four years, the newspaper lost almost 50 per cent of its total advertising revenues. In 2007, the paper had £22.5m advertising revenue. Just four years later, it had £11.4m.

All other revenues were also falling. Newspaper sales – the money from selling copies of the paper – came down from £5.7m to £4.3m. The presses had closed in 2009, bringing revenues down from £6.5m in 2007 to zero in 2011. And ‘other’ revenues fell from £1.6m to £500,000 in the same period.

In all, revenues had fallen by £20m from £36.3m in 2007 to £16.2m four years later. The sheer size of the £20m fall was catastrophic when compared to the company’s annual profit.

In the 15 years to 2007, the company had declared £7m-£10m profit – without drastic action, the company would have been making significant losses by 2009 and would have lost at least £10m in 2011. But the company had seen all the signs in 2006, and it set about slashing costs.

In common with local and regional newspapers across the country, the Leicester Mercury set about cutting costs in all departments and areas:

- Reduced the number of staff from 508 in 2005 to 107 in 2011

- Reduced the number of editions printed, from seven a day, to just one

- Moved to overnight printing at a printing press in Luton

- Closed its distribution arm, sending papers out with a wholesaler instead

- Reduced the size of the printed page

- Reduced the number of pages in the paper.

Staff numbers fell from 516 in 1996 to just 107 in 2011 and these cuts were made across the company.

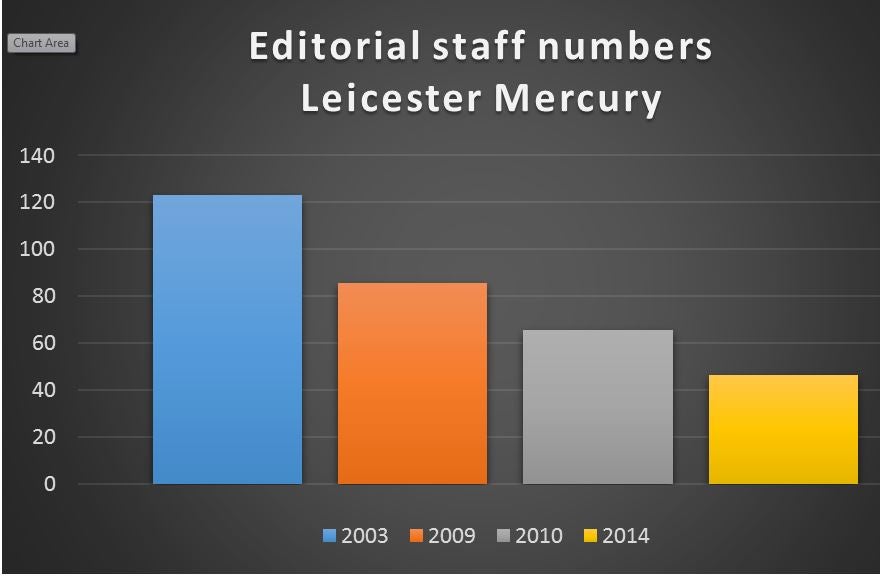

Editorial staff numbers had risen from 108 in 2000, to 109 in 2001, and then to 116 in 2002. In personal correspondence with the author, a former senior member of the editorial team says the number then rose to 123 in 2003. By 2011, there are no details given in the annual reports, but the overall number of staff in all areas was down to 107.

In early 2012, a letter released by the NUJ at Leicester suggested 11 jobs were about to be cut, bringing the number of journalists down to 44.

Numbers have fallen further since then with most of the features department being made redundant, along with four of the six photographers, bringing editorial staff down to 35, according to Press Gazette.

While the figures may be out by one or two at either end, it is clear the editorial team has fallen by more than 70 per cent in the past 13 years.

Interviews with current and former journalists at the Mercury’s sister paper, The Nottingham Post, support this, showing the number working in the editorial department had fallen from more than 120 to 46.8 by June 2014.

Both newspapers were previously owned by Northcliffe Media Group, before transferring to the newly formed Local World group in January 2012.

As most cost-cutting was driven centrally by group directors, it is likely the two newspapers – which were similar in both size and geography – would have been treated in much the same way as each other.

At the Leicester Mercury, in the ten years to June 2014, overall editorial staff fell by 63 per cent, the number of reporters reduced from 30 to 14.6 (about half). The number of editorial staff has continued to fall since then.

Reporters are the people responsible for the public interest reporting – the people who underpin local democracy and uphold the principle of open justice, or, at least, they should be.

While the number of specialists has hardly changed, the number of general reporters has almost halved, and the number of district reporters has fallen to zero. This is a pattern repeated at dozens of local newspapers across the country. Putting aside the specialist for now, it can be seen the number of reporters on the Leicester Mercury fell from 22 to just seven.

In 2015, thanks to a bursary from the University of Derby, undergraduate student Pete Salter interviewed about 40 current and former court reporters to find out how court reporting was changing.

Most said the number of journalists in court had reduced in recent years. Almost all agreed this meant important stories were missed.

In a survey by the Press Association and the Justices’ Clerks Society in 2010, almost 80 per cent of clerks said local newspaper coverage of their courts had declined, and almost two-thirds said they ‘rarely’ saw a reporter in their court.

Although it is clear the Mercury’s coverage of courts in the city of Leicester has reduced over the past five years, they still have a full-time crown court reporter and occasionally send a general reporter to the magistrates’ court.

However, another cost-cutting measure has had a far more drastic effect on the coverage of courts up and down the country. As noted above, the number of district reporters employed by the Leicester Mercury has fallen from 10 to zero since 2009.

This is as a direct result of the newspaper moving from producing several editions a day to a single edition printed overnight.

Traditionally, local evening newspapers had two sorts of editions: timed editions in the core circulation area; and geographic district editions. The district editions would usually carry the main news from the core circulation area, along with several change pages (usually including the front page) dedicated to news from the given district.

To produce this, most evening newspapers had their own presses and would take much of the day printing the various editions and distributing them. As we have seen, the Leicester Mercury closed its presses in 2007 (with the loss of 117 jobs) and switched its printing to Derby and Cambridge, and then later to Luton.

However, the Mercury was not the only newspaper closing its presses. Papers in Hull, Grimsby, Lincoln, Liverpool, Aberdeen and numerous other cities did the same.

Former newspaper editor and owner, Chris Oakley, said: “Centralising printing at as few sites as possible brings immediate large cost savings and ensuring the press runs for 24 hours a day is the most cost-effective use of an expensive resource, even though it almost inevitably means titles have to be printed at inappropriate times and with deadlines that will, over time, damage sales.”

The issue this created was the few remaining print centres were now printing multiple daily papers and the only way to do this was to reduce each paper to a single edition as it was time-consuming, and expensive, to stop and start a press several times for different editions. As a result, geographic district editions have all but disappeared throughout the UK.

As newspapers reduced to a single edition, news from outlying areas was perceived as not interesting enough to be carried in the newspaper where most readers were in the core city area.

As a result, the news from district areas – and the people who provided it – lost value. In Leicestershire, for example, district reporter Shirley Elsby had worked for the Mercury for almost 35 years. She spent more than 30 years at the paper’s Hinckley office, but, in 2011, she was made redundant and the Hinckley office was closed. Elsby had gone to Hinckley Magistrates Court at least twice a week, and told us in an interview:

“The daily paper is not covering the town. I think with the Mercury their city readership is still relatively strong but certainly in this district it is negligible, I would say. They don’t cover the courts, they don’t cover the councils unless a big story comes to their attention and it is strong enough for them to be bothered.”

This is borne out by a study of the Mercury’s coverage of Hinckley. It would appear the newspaper did not attend a case at Hinckley Magistrates Court for more than 12 months. The few cases which were covered were re-writes of council press releases. We found a similar story when we looked at coverage of the local council. Elsby said: “I don’t think anyone is keeping an eye on the court and council to hold them to account.”

This is a story repeated up and down the country.

Gordon Wilson, who recently retired after spending more than 35 years in the local press, had carried out various senior roles at the Derby Telegraph, latterly as night editor. In an interview, he told us regional dailies had ‘retreated and gone back to their core areas.’ He added: “The level of news in the Derby Telegraph circulation area, be it Belper, Melbourne or Ripley, is far more superficial than it was 20 years ago when we did specific editions.”

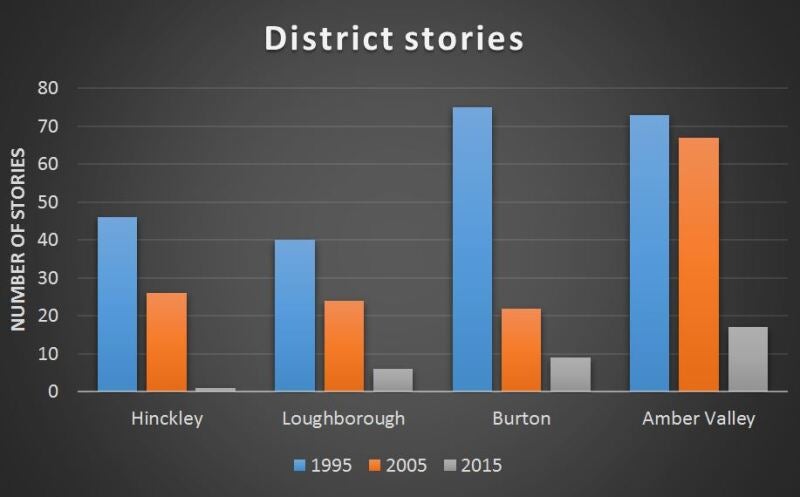

In a review of content in the Leicester Mercury, the survey found the number of court, council and crime stories from Hinckley during the same week in 1995, 2005, and 2015, had fallen from 46 to 26 to one. The situation was similar for stories about Loughborough, falling from 40 to 24 to 6. A look at the Amber Valley district area of the Derby Telegraph, found the number had fallen from 73 to 67 to 17. The decline was similar in Burton (75 to 22 to 9). Across the four areas in the two newspapers, the number of stories had fallen from 234 in 1995, to 139 in 2005, and just 33 in 2015.

It is clear the catastrophic reduction in the key revenue categories for regional papers has forced them to cut staff numbers by far more than has previously been reported.

This, combined with other cost savings, particularly the closure of district editions, has led to hundreds of towns up and down the UK losing their daily newspaper coverage, with the number of stories falling by more than 85 per cent.

The migration of revenues away from newspapers is a systemic change with little or no chance of local newspapers ever being able to afford to return to a situation where they can cover district towns as they did until ten years ago.

This is an edited extract from Last Words? How Can Journalism Survive the Decline of Print? Edited by John Mair, Tor Clark, Neil Fowler, Raymond Snoddy and Richard Tait Abramis Academic Publishing Bury St Edmunds £19.95. January 2017. Available for £15 to Press Gazette readers from Richard@abramis.co.uk

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog